What was the primary reason so many families migrated into the backcountry? ✅ Chất

Mẹo về What was the primary reason so many families migrated into the backcountry? Chi Tiết

Bùi Minh Chính đang tìm kiếm từ khóa What was the primary reason so many families migrated into the backcountry? được Update vào lúc : 2022-12-27 23:20:07 . Với phương châm chia sẻ Mẹo Hướng dẫn trong nội dung bài viết một cách Chi Tiết 2022. Nếu sau khi tham khảo tài liệu vẫn ko hiểu thì hoàn toàn có thể lại Comment ở cuối bài để Admin lý giải và hướng dẫn lại nha.Although the region west of the Blue Ridge Mountains had been occupied by American Indians for millennia prior to European contact and was fully incorporated into indigenous concepts of territorial organization, it did not harbor a large Indian population when colonial interests in the area first developed in the 1720s. In a series of conflicts over trade and natural resources that consumed much of the latter half of the seventeenth century, the Five Nations of the Iroquois League had driven most native peoples out of the upper Ohio and Potomac River valleys by 1700. In 1701, as the result of treaties with British and French colonial authorities (the so-called Grand Agreement), the Iroquois established their neutrality in the future imperial wars of European powers and resumed endemic conflicts with southern Indians, namely Cherokees, Creeks, and Catawbas. This situation polarized the political geography of the North American interior, setting northern Indians against southern Indians and leaving Virginia west of the Blue Ridge as a sensitive, highly strategic region in the geopolitical struggles of American Indians. The instability of this situation, aggravated by Indian war parties, diplomatic missions, hunting expeditions, and trading ventures, helps explain the European occupation of the region as a means of securing it within the British empire.

Nội dung chính Show- Colonial InterestSettlement and Commercial DevelopmentWhich of the following was most likely true of Americans who were influenced by the Enlightenment quizlet?Which group dominated the political and economic life of the seaport towns quizlet?Which of the following would most likely not be true of Americans who were influenced by the Enlightenment?What was the status of most slaves when Europeans traded for them in Africa?

Colonial Interest

Fry-Jefferson Map

It was in this context that referring to Virginia settlements west of the Blue Ridge as the backcountry made sense in the eighteenth century, when the colony had two frontiers. One was pushing westward with the expanding periphery of plantation settlement as Virginians migrated from the colony’s Tidewater region into the Piedmont. A discontinuous and spatially autonomous backcountry developed simultaneously as a southward extension of the Pennsylvania settlement into the drainages of the upper Potomac River beginning with the Shenandoah Valley. The former frontier was an articulation of a hierarchical plantation society, Anglo-Virginia culture, tobacco production, and African American slavery, while the latter was set apart by its more egalitarian social composition, ethnic diversity, religious pluralism, and small-farm, mixed grain–livestock economy that was dependent on neither tobacco nor slavery. These traits also identified the Virginia backcountry as an element of the much larger British colonial backcountry, which extended from central Pennsylvania to the Georgia uplands by the mid-eighteenth century.

The origins of backcountry distinctiveness are themselves traceable to deep and conflicting historic currents set powerfully in motion not only by the evident tensions between American Indians and Virginians over territorial claims, but also by the stress of imperial conflicts and anxieties over colonial security in a rapidly expanding slave society. Simply put, the character and significance of the Virginia backcountry was the product of political and imperial conflicts embroiling the entire Atlantic world in the eighteenth century. In the historiography of American frontiers, their establishment and development has been attributed to the land hunger of European settlers yearning for the economic independence of property ownership. The immense appetite of Europeans for land, with all its attendant wealth and status, certainly accounts for the westward push of Virginia planters onto the Piedmont in the eighteenth century, as new markets opened for tobacco throughout Europe and new marketing initiatives in the tobacco trade developed in Scotland, where the 1707 Act of Union with England opened trade throughout the British empire for the first time. In the western backcountry, however, the craving for land converged with the security concerns of imperial authorities in London and the colonial capitals. In this sense, the Blue Ridge was to the British colonies what the north of Ireland had earlier been to England—and, in a larger sense, what Gibraltar meant for British access to the Mediterranean.

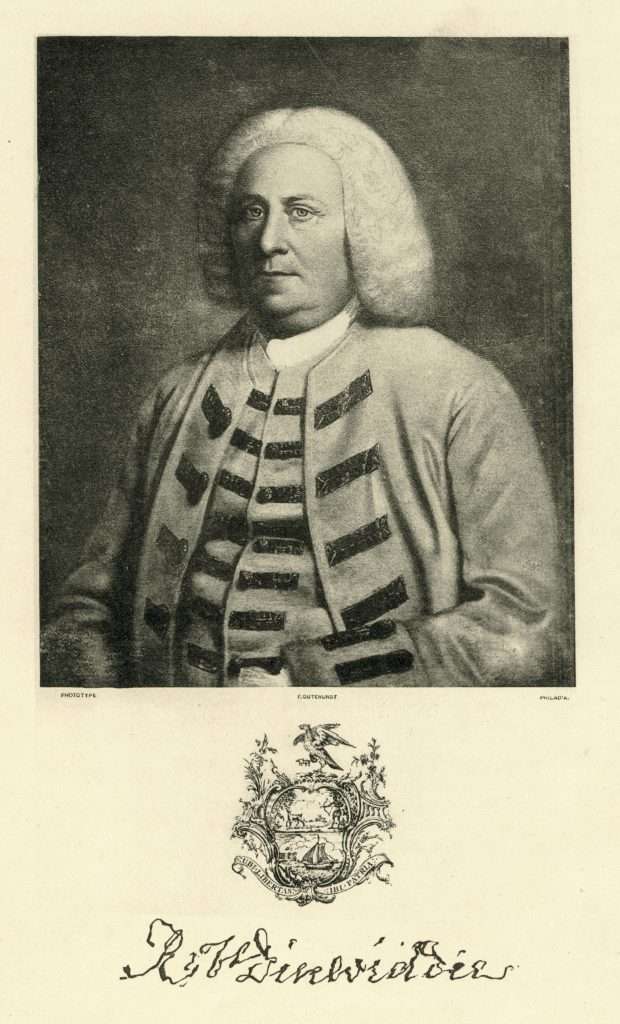

Alexander Spotswood

The strategic importance of the Shenandoah Valley was certainly on the mind of Virginia’s lieutenant governor Alexander Spotswood when he led an expedition of gentlemen soldiers there in 1716. Colonial rangers had recently discovered passes over the Blue Ridge that exposed the colony, as many feared, to attack by Indians and Frenchmen alike. Settlement of the valley by British subjects would secure and defend Virginia, not only in conflicts with northern and southern Indians, but also in the imperial struggles that had convulsed the Atlantic world for the previous three decades, during which New France had extended settlements and garrisons from Canada to Louisiana along the broad Ohio and Mississippi river systems. Also worrying Spotswood and his successors were claims by royal proprietors to western lands and the growing threat that runaway slaves might establish autonomous communities in the mountains and resist reenslavement, as did the maroons in Jamaica, with whom Britain was engaged in a protracted war.

The major push toward the British occupation of the backcountry began with a series of land orders totaling close to 400,000 acres west of the Blue Ridge, issued by Lieutenant Governor William Gooch between 1730 and 1732. Because most of the recipients—some of whom obtained orders for more than 100,000 acres—were Germanic and Scots-Irish immigrants from Pennsylvania, and because the lieutenant governor had mandated that they recruit one settler family for every 1,000 acres within two years as a condition of receiving their land patents, Gooch’s policy let loose a substantial migration of Pennsylvanians to the Virginia backcountry. By 1735 there were as many as 160 families in the region, and within ten years nearly 10,000 Europeans lived in the Shenandoah Valley.

Stark differences in ethnic and racial composition, religious disposition, agricultural economy, and labor organization set the society of frontier settlers dramatically apart from the culture of eastern Virginia. In the eye of colonial authorities in both Williamsburg and London, however, their Protestantism, self-sustaining small-farm communities, and lack of dependence on African American slavery rendered them ideal protagonists in a global struggle with Catholic nations such as France and Spain. In addition, they constituted a potential militia barrier in defense of eastern Virginia and a non–plantation settlement buffer against the threat black maroonage posed to a slave society. Thus, the distinguishing features of Virginia’s farthest frontier were owing not only to the appeal of land to diverse European peoples, but also to the coincident uses colonial and imperial authorities were willing to put these peoples for strategic purposes in varied conflicts.

Settlement and Commercial Development

Robert Dinwiddie

Upon their arrival in the backcountry the settlers, as Virginia lieutenant governor Robert Dinwiddie later put it, “scattered for the Benefit of the best Lands.” The result was open-country neighborhoods of dispersed but usually contiguous farmsteads, each enclosing about 300 acres with access to springs and water courses. Because the desire for land usually exceeded any preference for ethnic exclusivity, German, Scots-Irish, English, and Anglo-Virginian peoples intermixed in so-called open-country neighborhoods, consisting of dispersed but usually adjoining farmsteads of about 300 acres, with access to springs and watercourses. Ethnic groups often maintained their identity for several generations through endogamy (marrying within the group), but local trade engrossed entire communities in frontier exchange economies, ethnicity notwithstanding. Households engaged each other continually in the commerce of agricultural surpluses, labor, and artisan services, trading a few spare bushels of wheat, corn, or apples for a day’s work or a bit of blacksmithing with a neighbor. In the absence of hard currency, commercial exchanges were measured by the calculation of debits and credits in book accounts. This kind of reciprocal economic development on an isolated frontier was encouraged further by a long period of largely peaceful relations with American Indians, with whom a trade in skins and furs advanced everyone’s interests.

But the nature of backcountry life changed dramatically between 1750 and 1760. In a long-term trend that started in the mid-1740s but accelerated sharply in the 1750s, prices for wheat and flour in the Atlantic economy began to rise. Flour exports from Philadelphia increased sixfold as this prominent port city captured control of the provisions trade with the West Indies and southern Europe. Connected to western Virginia by the Great Wagon Road, one of the longest single roads in early America, Philadelphia transformed the economy and landscape of the backcountry frontier. By late in the 1760s, wheat had become the Shenandoah Valley’s primary staple crop: a farmer in the lower valley could grow wheat, grind it into flour a local mill, sell it on the Philadelphia or Alexandria market, and realize a profit against considerable transportation costs.

The proceeds of flour production then enabled frontier households to participate in a consumer revolution that transformed the British empire into an empire of goods by the end of the eighteenth century. Fine imported wares began to appear on the tables and in the sitting rooms of backcountry houses, often newly enlarged or rebuilt according to the international design principles of Georgian symmetry, balance, and order. What modern architectural historians call an I-house—a two-story dwelling with an exterior end-chimney—became an archetype of architectural improvement in the rebuilt landscape of the old backcountry, by now a settled society.

Defining the transformation of Virginia’s backcountry landscape during the last third of the eighteenth century was the development of towns. Although most agricultural commodities—livestock as well as flour— left for market from dispersed farm gates and mills, it was the credit recorded in the accounts of town merchants and the imported goods offered in their markets and shops that concentrated the robust commerce of the backcountry in its towns. A second significant development that stimulated town founding and growth was the global struggle of the Seven Years’ War, which embroiled the backcountry in armed conflict from 1754 to 1763. Pontiac’s War (1763–1765), waged by Indians against the British in the Illinois and Ohio countries, also engrossed the backcountry in fear and fighting. Fleeing outlying farms and unfortified open-country neighborhoods, farm families sought the security of garrisoned towns such as Winchester. There, and in least five new towns founded during the conflict, the economic demand created by refugees and the labor they could provide intermingled with the needs of soldiers and camp followers to stir a dynamic economic mix out of which true market-town economies emerged.

Legacy

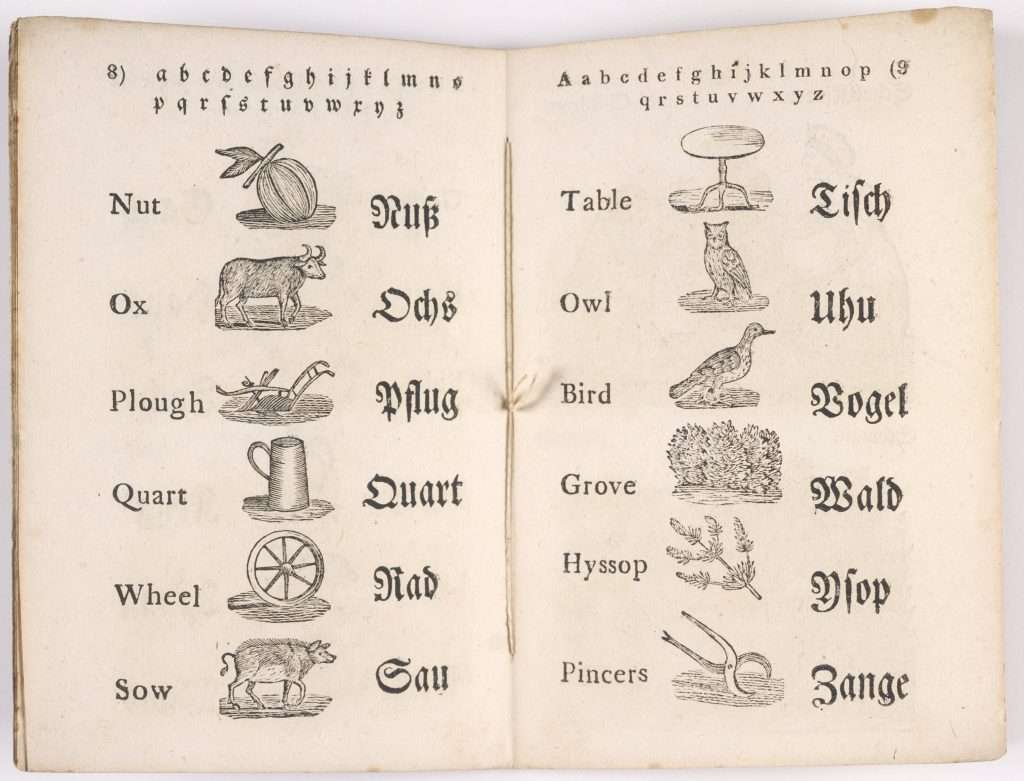

A B C-und Bilder-Buch

If the open-country neighborhoods and exchange economies characterized the first phase of backcountry settlement, then a town-and-country settlement system was the product of a market revolution in agriculture, the improvement of the landscape, and the development of market towns with an attending hierarchy of rural hamlets and local villages. The emergence of this system by the close of the eighteenth century marked the end of the frontier period in western Virginia. What happened after the backcountry ended, however, was anything but backward. So productive was the agricultural economy west of the Blue Ridge, with a bountiful commerce pouring out of the region as profits in the flour and livestock trades and into it as imported goods in the consumer revolution, that the region came to be characterized as a “New Virginia” of high farming and market-town commerce. Enduring sectional patterns emerged as Old Virginia remained committed to slavery, tobacco, and the politics of fiscal conservatism. The dynamic town-and-country economies west of the Blue Ridge predisposed its peoples to favor banks, internal improvements, and other forms of economic modernization. They voted Federalist in debates over the Constitution and actively supported the new central government whose economic power to integrate interstate and international commerce constituted the lifeblood of western Virginia in the nineteenth century. Thus the backcountry became a model for trans-Appalachian frontier development. Its significance as a region remains in the heritage of a backcountry to what Virginia was in the eighteenth century and in a forecountry to what the United States was to become thereafter.

Which of the following was most likely true of Americans who were influenced by the Enlightenment quizlet?

Which of the following was most likely true of Americans who were influenced by the Enlightenment? They would be from the educated upper class.Which group dominated the political and economic life of the seaport towns quizlet?

15. Which group dominated the political and economic life of the seaport towns? enterprising merchants worked to organize and control the commerce of the surrounding region.Which of the following would most likely not be true of Americans who were influenced by the Enlightenment?

Which would most likely NOT be true of Americans who were influenced by the Enlightenment? they would understand knowledge as valuable for its own sake, independent of any practical usefulness.What was the status of most slaves when Europeans traded for them in Africa?

What was the status of most slaves when Europeans traded for them in Africa? Captives of war. Tải thêm tài liệu liên quan đến nội dung bài viết What was the primary reason so many families migrated into the backcountry?